The other day, Taylor Marshall tweeted, um, a bunch of things. But stay with me! This post isn’t really about him. I just don’t know how else to talk about what I want to talk about, except by starting with what he tweeted.

.

First, apparently understandably distraught over an interview with McCarrick’s first victim, he tweeted some foul garbage about how gay it is that seminarians had a gingerbread house-building contest. Seriously, he did the f*ggy lisp and all, and included a name and photos of the men engaging in this “effeminate and puerile” activity, because that’s how you act when you’re a serious Catholic theologian and scholar.

It was wildly gross and offensive (and since he asked, can you imagine Basil and Gregory tweeting at each other?), and insanely insulting to gay people in direct contradiction of the catechism.

.

But it also threw into high relief how poorly so many people understand what it means to be masculine. Many of his followers apparently believe that any time you’re not studying Latin or logic, building fires, chopping something, or shooting something, you’re a whisker away from of sliding into that dreaded horror, effeminacy. In order to save the Church, we must stop having . . . gingerbread.

.

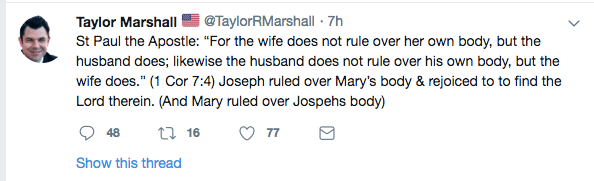

His tweet was thoroughly trounced by many others, so I left it alone. But then he followed up with something that really nagged at me:

And that sounds very much like what Joseph knew. He listened, a lot. He decided, out of love, not to fight things that had already come to pass. He worked with the system as long as he could, and when it wasn’t working, he gathered his family and ran away. He was willing to play a supporting role. He decided not to insist on taking what he could reasonably argue was rightfully his. And he was silent. In other words, Joseph’s behavior in the Gospels is like what we today normally think of as feminine — trusting, waiting, nurturing, self-sacrificial, chaste, modest, and quiet. This may account for

how weirdly effeminate he looks in so much religious art, and it probably accounts in part for Marshall’s weird attempt to put Mary’s fiat in Joseph’s hands: Because he doesn’t behave in a way that checks off boxes in our modern understanding of masculinity.

.

We get St. Joseph wrong because we grasp that he is not what we commonly think of as masculine; but correct our mistake by assigning to him what we wrongly think of as feminine, or by refusing to face how wrong we are about what it means to be feminine. Mary’s behavior is what we should think of as feminine; but it’s so hard to grasp that we saddle her with a simpering passivity, turning her into a virgin too fragile to deal with men, rather than a virgin strong enough to deal with God.

.

Hell if I know what it all means, except that most of what we commonly think of as masculine and feminine is garbage, which probably accounts for why so many people think it doesn’t mean anything. In other context, my sister Abby Tardiff said this (and this was just part of a Facebook comment she dashed off, not some polished work of prose):

.

[S] ex and gender have to be understood first as cosmic paradigms. So, “feminine” doesn’t mean “like a woman.” It’s the other way around. A woman is someone who embodies the eternal archetype of femininity. But she won’t do it completely, because she’s an instantiation [a representative of an actual example], not the archetype itself. She’s a particular, not a universal. Also, her instantiation of the feminine will filter itself through her personality, through tradition, through society, etc. For these two reasons, you can’t pin down any one characteristic that every woman has. Any time you try to say what characteristics women have, you’ll find exceptions (often me).

However, if you start from the archetype, and say (for example) that the feminine archetype involves the taking of the other into the self, then you can conclude that every woman is cosmically called to do this as well as and in whatever way she can. So the point is not to say what women are like, but what their vocation is.

.

Taylor Marshall and his ilk are rightly angry that McCarrick and others have so smeared and ravaged human sexuality with their crimes and perversions. But Marshall’s brutal, puerile urge to squash all men and all women into small and clearly defined boxes of masculinity or femininity is, in its way, just as disastrous. More than one abused woman has told me that, early on in her marriage, before the beatings began, her pious Catholic husband railed at her for not being sufficiently archetypically feminine, as if any one woman could or should be. As if he had married womankind, rather than an actual person. This is the trap Marshall et al fall into: They want individual human beings to be the embodiment of all of their sex (“all seminarians must be masculine”); but since no one can or should achieve that, they reduce an archetypal reality to a few small, individualistic traits, and then rage at anyone who doesn’t reduce himself to those traits, as if they’ve failed at being human.

.

It’s a way of making sense of the world, and it’s intensely depersonalizing. We do not love by making what is large small, and we do not love by railing at what is small for not being as large as the whole universe. But people who behave this way don’t think they’re being cruel to individual people; they think they’re being noble by upholding ontological truths. But first they have to squash those ontological truths into bite-sized pieces.

.

Dressed up as respect for God’s creation, this way of thinking turns men and women away from our vocation, which is, in our particular ways, to be open to God: To be feminine in relation to God.

.

Yes, that looks different for men and for women, and it looks different for for one particular women compared to another, and one particular man compared to another; but in some very broad way, this is the true feminine, what both Joseph and Mary did.

.

I saw it myself yesterday, dozens of times, at Mass, at the Eucharist, men and women. They walked up to the front with all the burdens and glories of their particularities, and then opened up to receive God. How? Because He alone can take ontological truths and make them, as it were, bite-sized. He has made small what is larger than then universe, larger than masculine and feminine. Love makes itself small. Never to make others small.

.

Our vocation is to be open like Mary and open like Joseph, and neither one of the two of them look like anything I’ve ever seen before on this earth, except in brief flashes like at the altar rail. Hell if I know what it means. My kids were asking me about the Second Coming today, and all I could say was everyone who thinks they know what they are talking about is in for a surprise.